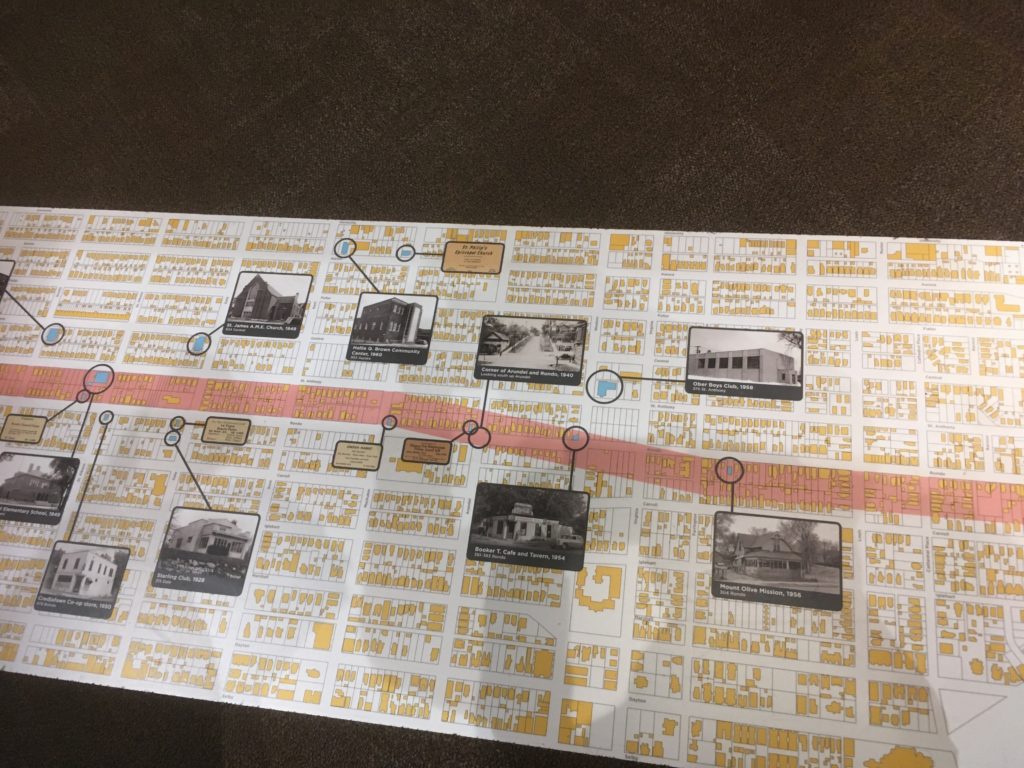

A highlight of a recent visit to Minneapolis-St Paul was a tour of the Rondo neighborhood by Steve and Catherine Dickinson who came to live there in 1979 and used their home as an Initiatives of Change center. For decades in the 20th century Rondo was the thriving heart of the black community. Many who arrived from the southern states made their homes there. But it was largely demolished in the period between 1956 to 1968 due to the construction of 1-94. More than 500 families and businesses were displaced.

In 1952, the St Paul Housing and Redevelopment Authority had targeted the area for urban renewal and removal of “blighted” properties, thus making it easier to rationalize putting the freeway through the area. By the time Dickinsons arrived the streets were dangerous and their neighbors included drug dealers and all-night clubs.

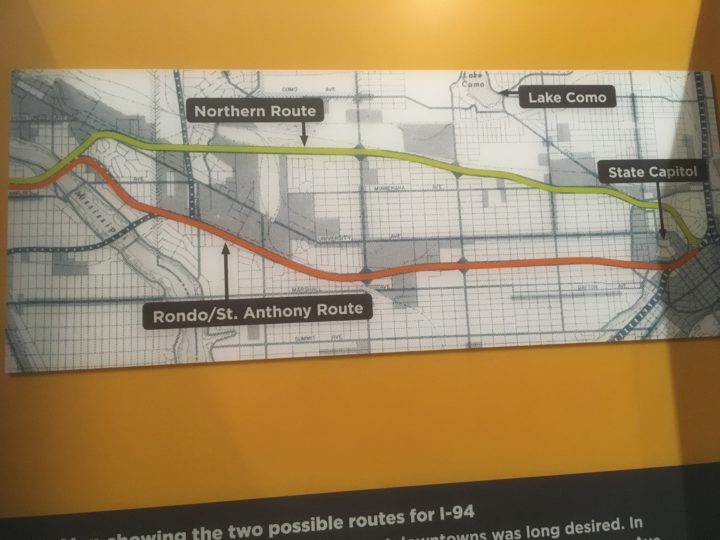

The freeway could have been built on an alternative northern route along abandoned rail tracks, which engineers preferred, but business and political leaders chose the direct route through Rondo. This pattern was repeated in many US cities. In Richmond, Virginia,where I lived for many years, the Jackson Ward neighborhood, which had been the home of doctors, lawyer and teachers, was bisected in the 1950s by the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpikc. Although the proposed route was defeated by popular referendum, city leaders created the Richmond Metropolitan Authority which was able to push through an amended proposal. Hundreds of homes, businesses, community centers and churches were destroyed. Many residents ended up in public housing. As in the case of the Rondo neighborhood, an alternative route for the highway could have been chosen but power and money won the day.

In 2016 the St Paul Mayor Chris Coleman and the MNDOT Commissioner Charlie Zelle made a formal apology to the Rondo neighborhood. Through sustained efforts of community leaders Rondo is again beginning to flourish with annual festivals, a focus on public history and rehabilitation of fine old houses that had been abandoned.