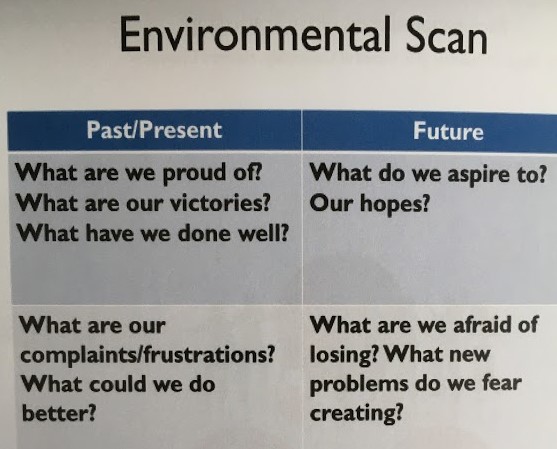

In workshops with diverse and polarized community groups, we often use an “environmental scan” to map what is going on in the room. Using four quadrants we ask participants to write and post their individual responses to four questions: What are we proud of, or what are the successes in our community? What are our complaints or frustrations? What are our hopes and aspirations? What do we fear losing, or what new problems do we fear creating?

The answers to the first two questions are usually easy to answer and often predictable. They are what everyone talks about all the time. And it is also true that in many ways even people of very different backgrounds share similar hopes and dreams: security for their families, safe neighborhoods, clean environment, good education for their children, and well-paying jobs.

It is the fourth question – the issue of loss – that we must pay close attention to, because it is usually fear of loss that is the underlying cause of tension and distrust.

A sense of loss, both real and perceived, is playing out in many democracies across the world. For example, as Lawrence Summers, who headed Obama’s National Economic Council, said recently, “There is probably no issue more important for the political economy of the next 15 years, not just in the United States, but around the world, than what happens in the areas that feel rightly that they are falling behind and increasingly left apart.”

Even greater than actual economic loss is the threat of loss of cherished identities, dignity, traditional values and way of life in a rapidly changing global culture. Fear of not being heard or respected is just as powerful as fear of loss of material wealth or stability.

As people face an uncertain future in a rapidly changing environment, false narratives can easily take hold that are not easily countered by actual facts. Take the issue of migration. As the Economist magazine wrote recently, “Few migrant skeptics can cite harm that a foreigner has done to them but nationalists around the world swap anecdotes, some of them true, that reinforce the fears.” Reputable studies show that immigration benefits everyone. The Economist quotes Michael Clemens of the Centre for Global Development who estimates that if everyone who wanted to migrate were able to do so, global GDP would double. Over a lifetime a typical immigrant from other parts of Europe to Britain can expect to pay £78,000 more in taxes than he or she receives in benefits. Australia with 29% of its population born abroad has one of the most successful economies in the world. But such data means little to those who feel the pace of change threatens all that they hold dear from the past. This becomes fertile ground for demagogues and populists using the tools of social media.

In a December 9 column in the New York Times, Peter Baker quotes Robert Wehner, a former strategic adviser to President George W. Bush: “The danger is people come to believe that nobody is giving them the facts and reality, and everybody can make up their own script and their own narrative…truth as a concept gets obliterated because people’s investment in certain narratives is so deep that facts simply won’t get in the way.”

Few of the blue-collar workers who voted for Trump in 2016 really believed that he would restore the coal mines or steelworks to their former prominence. Their vote was largely a protest at a perceived liberal elite who have lost touch with ordinary Americans and the bankers of Wall Street who plunged the country into recession and then walked away unpunished.

For someone like myself who is stunned by the overwhelming support for Trump among evangelical Christians and conservatives, I found it illuminating to read an October speech by the Attorney General, William Barr, at Notre Dame University in which he decries the “growing ascendancy of secularism and moral relativism,” and points to the “wreckage of the family,” sexual license, an illegitimacy rate of 70% in some urban areas, the epidemic of suicides and depression, and the anger and violence among young men. He highlights “the force, fervor, and comprehensiveness of the assault on religion we are experiencing today.” He continues, “This is not decay; it is organized destruction. Secularists, and their allies among the ‘progressives,’ have marshaled all the force of mass communications, popular culture, the entertainment industry, and academia in an unremitting assault on religion and traditional values. These instruments are used, not only to affirmatively promote secular orthodoxy, but also drown out and silence opposing voices, and to attack viciously and hold up to ridicule any dissenter.”

In reality, of course, there was much about traditional culture that was deeply wrong. In many ways the US is a far more just, equal and less prejudiced country than it was 50 years ago. But one does not have to agree with Barr’s politics or his analysis of today’s culture to appreciate the genuineness of his concern, or even fear, for the country. There is validity in his call for a greater focus on individual moral responsibility rather than relying on government intervention. In my view, we must work for structural change and inner change at the same time. We need just policies and personal responsibility.

There is a wise saying that “fear is a liar.” Of course, fear is sometimes an important survival mechanism, but when it becomes a controlling force it causes us to make bad choices. Hence, out of fear of loss millions of dedicated Christians are prepared to support the most morally corrupt president in living memory in the hope of securing conservative justices for the Supreme Court who might be more inclined to support further restrictions on abortion.

But those on the liberal side are often far too reluctant to directly address moral issues for fear of being seen as politically incorrect. They accuse those who talk of personal responsibility as blaming the victim. They hesitate to seek common ground or tolerate potential sensible compromises, fearing that hard-won gains will be rolled back. They also predict an apocalyptic future if the “other side” keeps control.

According to my Internet search, “fear” is spoken of over 500 times in the King James Version of the Bible. And “Fear not!” is the most repeated command. In church last Sunday we heard the words of Isaiah: “Say to those who are of a fearful heart, ‘Be strong, do not fear! Here is your God.” The liturgy continued, “We give you thanks and praise, O Lord, for bringing us good news that calms our hearts when we are fearful and makes us sharers of joy.”

Suppose each of us were to take time to sit and talk with someone who represents a very different background or point of view and ask them: What are you most proud of? What are your concerns? What are your greatest hopes or deepest longings? What do you most fear losing? It might lead to deep storytelling about families and communities, and maybe some surprising common ground, perhaps even some laughter. By honoring each other’s journey without judgment, in some small way we might begin to break through our preconceptions, build relationships, and become sharers of joy rather than purveyors of fear.