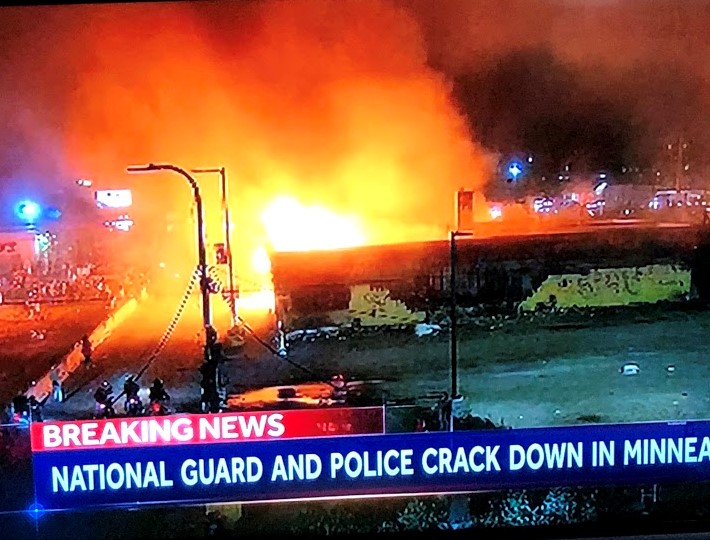

On the day that the US launched two astronauts on SpaceX Dragon, protests, riots and violence erupted in more than 70 cities following the killing of an unarmed black man by a white police officer in Minneapolis. Perhaps nothing illustrates more starkly the gap between our extraordinary technical prowess and our moral failure as a nation to value the humanity of every human being. As our most brilliant researchers race to find a vaccination for COVID-19, we seem unwilling – not unable but unwilling – to provide basic health care, quality education, affordable housing, a living wage, and equal justice under the law to all our citizens regardless of race or ethnicity.

We have been here before and we will be here again until as a nation we come to terms with the roots of our division. My friend Mike McQuillan, an architect of the Crown Heights Coalition in Brooklyn, New York, in the early 1990s, likens America’s racial issue to “an old coffee pot that keeps percolating.” Every few years something happens that brings the vexed problem to the surface. Unplugging the percolator requires courageous conversation and honest acknowledgment of the underlying sources of distrust.

Clearly, we need systemic reform to root out the inherited culture of racism in police forces which have become increasingly militarized. However, many local police forces have been working diligently on their training. In several cities they have actively encouraged peaceful demonstrations. In Flint, Michigan, the sheriff took off his helmet and walked with the crowd. In Miami, police apologized to protesters and prayed with them.

My colleague Tee Turner has supported the community of La Grange, Georgia, in their community dialogues which included police officers. One participant was LaGrange’s police chief, Louis M. Dekmar. He subsequently extended a public apology to Ernest Ward, the local president of the NAACP for a lynching 77 years earlier, when a black man was dragged from a jail cell by masked white men.

The apology made national news. The chief has ensured that police take part in every workshop. Largely as a result of these experiences, LaGrange hosted a state-wide conference of police

But let’s be clear. We cannot lay all the blame on police who still harbor entrenched conscious or unconscious bias. The inequities and injustices America faces are not just the work of overt racists. They are also the result of the daily choices and priorities of millions of people. Local police are often asked to operate in communities traumatized by decades of public policies enacted by locally elected governments.

Bishop Michael Curry, in his Pentecost Sunday sermon, said that the real pandemic is spiritual in nature. We have an “pandemic of selfishness, of self-centeredness” in this country. The presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church said this pandemic “is more destructive than the virus.”

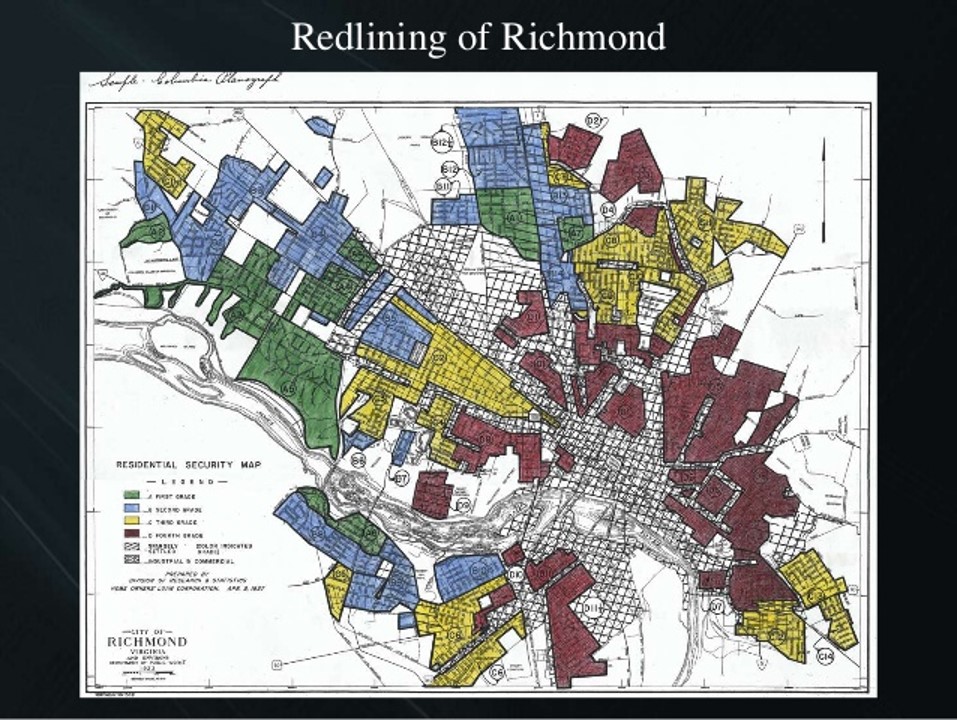

We have created gated communities with armed security to keep out “those people.” We resist paying taxes to support people who are different from us. Until the late 60s, the practice of redlining denied home mortgages to minority communities, resulting in concentrated poverty in many urban centers. When the housing market crashed in 2008 those same communities were victims of predatory lending.

Myron Orfield, a civil rights professor at the University of Minnesota, notes that the number of heavily de facto segregated schools (90% nonwhite) in Minneapolis-St Paul rose from 11 in 2000 to 170 in 2019. A 1974 Supreme Court decision allowed Detroit to be protected from a metropolitan desegregation plan that set in motion a national trend which, as the social psychologist Tom Pettigrew puts it, allowed local jurisdictions to act as “racial Berlin Walls.” In Richmond, Virginia, where our sons went to school, two-thirds of the white population deserted the public schools when the city attempted to integrate them through busing. This pattern was repeated across the country.

The stalking horse for race is economic class

Rev. Ben Campbell, a leading voice for racial justice and healing in Richmond for decades, emailed me: “The issue is race, but the stalking horse for race is economic. That is to say, we have gotten rid of the overt discrimination of Jim Crow. We do still have personal racism – at its extreme like the cops who did the murder of Mr. Floyd. But the major mechanism for racism is not simple racial prejudice but economic class.”

For the past 50 years the American financial industry has been pulling money out of every part of the economy, with the result that the reserves are gone from a significant number of businesses, and that company after company has been bought and folded by hedge funds.

Our demand for the cheapest possible consumer items – the cheapest hamburger and least expensive fashion items – and the insatiable drive for short-term profit means that wages have increased only 16% in 50 years and benefits have decreased, while the income of persons living on investments has increased 300% in real terms.

Costs of health care and university education have risen astronomically. Housing costs are out of control, with 40-50% of the population paying more than 33% of their income for housing and utilities and 15% paying more than 50%.

“Because of America’s historic racism, the impact of this is enormously racist,” says Campbell, who is white, “but the causality is economic, not racist.”

This is the true violence that is wreaking havoc on the country. Rev. Dr. Paige Chargois, a Richmond African American pastor and racial healing warrior writes, “Folks are decrying buildings being defaced or broken into. Few ever consider the extent to which black lives are broken into, defaced or destroyed – physically, economically and emotionally.”

The long-term impact of discrimination combined with the emotional and physical stress of living in a racialized society makes the minority population even more vulnerable to the virus. Dr. Gail Christopher, the executive director of the National Collaborative for Health Equity, founder of the RxRacial Healing Movement and former senior advisor and vice president of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, is a health practitioner. She points to the devastation of the COVID-19 infections and deaths among people of color.

“Counties with significant Black populations account for 60 percent of recorded deaths and 50 percent of recorded COVID-19 cases,” she writes in The Crisis Magazine.

“Could this pandemic help us to finally see and understand the dire consequences and overwhelming implications of racism I have observed in my decades of clinical practice as a health care provider?” She observes that because of the way the virus is transmitted, “the very air we breathe makes us interconnected and interdependent.”

Campbell remarks on the generational change. “A lot of action [protests and demonstrations] is coming from white youths. They have grown up in the suburbs. Their commitments are intellectual. Raised on social media, their experience is paper thin, and their positions are prematurely dogmatic and extreme. The Civil Rights movement had plenty of arguments about strategies and nonviolence from King to SNCC to Malcolm X. But the goal was clear. It was beating back legalized racial discrimination. The goal here isn’t clear. An end to police violence – sure – but the rage is about much more than that, and it differs from town to town; and if the goal isn’t clear, the ability to focus the strategy and keep out the crazies is fiercely diminished.”

Personal and collective transformation

This is not a simple issue of right or left. If Bishop Curry is correct in his analysis, we all have work to do. We all need to take an honest look at our priorities and assumptions and be willing to lay aside our pride, our fears, and our selfishness. As Curry reminded us, we wear masks not to protect ourselves from the COVID-19 virus but to protect others.

Rev. Paige Chargois, says, “Quit quoting MLK, Jr. as though waving magic wands over the protests. If his words meant anything to you, you would be living it!” She continues, “I’ve been reading about Pope Francis and came across this statement: ‘Unless [we] offer the BEST of [ourselves] the world will never be different.’”

Gail Christopher concludes, “The societal prescription for this nation…is first a relational one – a transformation in how we see, perceive and value all people.” This “collective change of heart” can generate new priorities.

Recent events may overshadow positive work that has been going on for decades. In 1992, as Los Angeles smoldered after the uprising sparked by the savage beating of Rodney King by police officers, community leaders from across America gathered in Richmond, Virginia to begin to formulate a strategy to encourage the kind of honest conversations that McQuillan advocates and launching the movement known as Hope in the Cities. In the years since, many organizations and communities across this country have been taking creative actions to address the wounds of racial history and bring diverse groups together, building relationships of trust.

This is hard, long-term work, often unreported by the media. But as Gail Christopher writes, ‘Hopefully, our nation’s people can use the shocking pain and suffering from this pandemic to find the courage to unite and move forward together, as our shattered society seeks to right itself and to move beyond the denial that has shaped our present. Government, corporate, civic, spiritual and community leadership …must be committed to supporting collective healing and transformation.”