We are approaching the end of two traumatic years. For many life will never be the same. At the time of writing, the US death toll from Covid has reached 800,000. One hundred and sixty thousand children have lost at least one parent or caregiver. Racial inequity, political polarization and economic anxiety touch all of us in different ways. Unprecedented tornadoes have devastated lives and communities. Research by the Boston School of Public Health indicates that 32.8 percent of the population is experiencing some form of depression.

This is traditionally a season of thanksgiving, celebration of light and new birth. That may be hard for many. So I am encouraged by reading two books that give valuable perspective and practical advice.

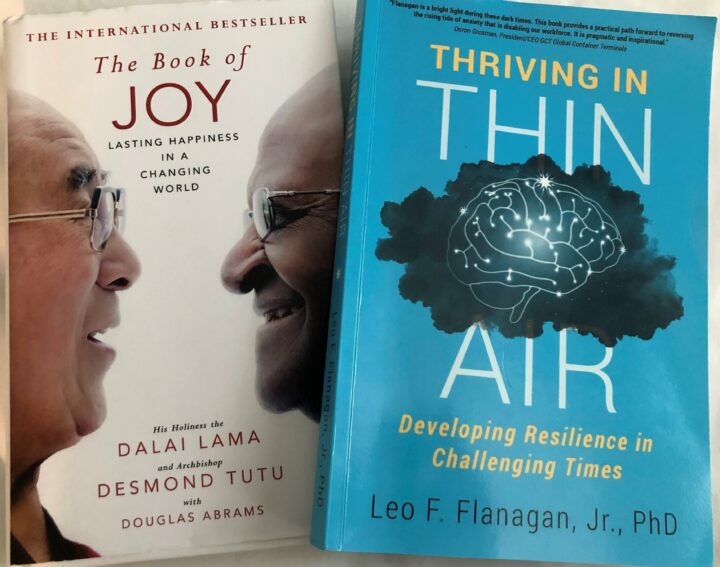

Leo Flanagan, Jr., founder of the Center for Resilience, has 35 years’ experience as a clinician, teacher, and executive coach. He has consulted for major corporations and led on-the-ground responses to disasters such as 9/11, the Newtown School shootings, and Hurricane Sandy. His book, written and published against a background of the Covid epidemic, Black Lives Matter demonstrations, and an assault of the US Capitol, is entitled Thriving in Thin Air: Developing Resilience in Challenging Times. (Full disclosure: his son-in-law, our youngest son, Andrew, edited the manuscript.) As he notes, anxiety and depression are experienced “because we are surrounded by external threats with no clarity as to how they will end and a lack of personal choices (i.e., control) in how we can respond to them.”

The good news is that we can rewire our brains to enable us to thrive amidst the adversity and uncertainty we are surrounded by. “Trying to survive in the thin air of Covid-19 and amidst racial and social injustice and financial needs keeps us focused on surviving rather than thriving. But this is the perfect time for all of us to recreate our set of balanced goals.” His book offers a 10-point framework and tools for doing just that. I will highlight a few of the many important principles and steps that resonate with my own experience as a facilitator and community builder. One simple one is a “gratitude exercise” as part of a “pragmatic optimism routine.” At the end of the day, write down five things that went well, however small. These will compete with the negative memories or triggers in the amygdala, the part of the brain that perceives our emotions and remembers them while we sleep.

Another factor is focus. As well as breathing techniques, he recommends pausing for 15-30 seconds before entering a new environment, short and longer times of meditation and – perhaps most importantly – resist looking at your smartphone before the first hour of work! Many people are overwhelmed and distracted “before their feet hit the bedroom floor.” A Harvard study shows that we are distracted 47 percent to the time.

A third key factor is building empathy by “investing in relationships so that you can see a situation from someone else’s point of view and understand and share their feelings about the problems or challenges they face.” This requires us to be curious: Ask questions and listen intently for words, tone and body language; acknowledge what you hear, stay open and don’t interrupt; be yourself and be comfortable talking about yourself. His chapter on fact-based decision-making includes a tool that helps us recognize and overcome confirmation bias that overweighs information that agrees with our beliefs and that may be influenced by conscious or unconscious racial and social biases. I was particularly interested in his “four most powerful questions” tool which he uses to support balanced goal-setting for work, family, health, spiritualty and community: What do you want? What are you doing? How is that working? What is your plan? This line of open inquiry is important because “as soon as you tell me I should or must do something, you trigger a set of neural networks whose purpose is to resist change…When you inquire/ask questions, you don’t erect a wall.”

There are many other valuable components in this road map for resilience, including the importance of sleep, and tips for self-control and self-reflection. Flanagan distinguishes between happiness and fulfilment. “Happiness come from experiencing and receiving things that are pleasurable. Fulfillment comes from engaging with your higher self.” He writes that in our our search for a meaningful life “you use your signature skills specifically to serve a higher purpose, which benefits others.”

I was interested to read Flanagan along with a book of conversations with the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a Changing World, written with Douglas Abrams, is a treasure of spiritual practices, many of which resonate with Flanagan’s experience as a psychologist and coach. As the Dalai Lama puts it, “From the moment of birth, every human being wants to discover happiness and avoid suffering…The ultimate source of joy is within us. The suffering from a natural disaster we cannot control… [But] many of the things that undermine our joy and happiness we create ourselves from the negative tendencies of the mind, or our inability to appreciate and utilize the resources that exist within us…we have the ability to create more joy. It simply depends on the attitudes, the perspectives, and the reactions we bring to our relationship with other people…there is a lot that we as individuals can do.”

Both the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Tutu have experienced trauma. The Dalai Lama faces the likelihood of never being able to return to his homeland from which he was forced to escape in 1959. Desmond Tutu endured decades under the oppression of apartheid and his country still suffers from unhealed wounds and socio-economic inequities. How do they both maintain such a spirit of joy and resilience?

One way of lessening personal pain, is a shift in perspective from oneself and toward others, a recognition that others are suffering as well and that we are all connected. This is the birth of empathy and compassion. Tutu tells us that it’s how we face all the things that seem to be negative in our lives that determines the kind of person we become. “If we regard all of this as frustrating, we’re going to come out squeezed and tight and just wishing to smash everything.” If we just look for happiness, we will find ourselves turning inwards. “It’s like a flower. You open, you blossom, really because of other people.” Lessening one’s self-absorption seems to be foundational to this approach. Both these spiritual leaders refuse to take themselves too seriously and have an infectious sense of humor.

But how to deal with intense sadness and grief, perhaps at a death of a friend or family member? Flanagan tells us that grief is a natural and necessary process and that avoiding it can lead to more suffering. We need to allow ourselves space to grieve. He also notes that sharing our grief can create bonds with others of very different backgrounds; and we can create meaning out of grief through acceptance and the need to move forward, making the world in some small way a better place. The Dalai Lama suggests we use our emotions as a way to generate a deeper sense of purpose. “If the one you have lost could see you, and that you are full of determination and hope, they would be happy.”

Hope is different from optimism. Tutu says optimism depends more on feelings than actual reality. “Hope is different, it is based not on the ephemerality of feelings but on the firm ground of conviction….To choose hope is to step firmly forward into the howling wind, bearing one’s chest to the elements, knowing that, in time, the storm will pass.”

Flanagan writes openly about his personal journey, including his struggle with PTSD after his work at Ground Zero in the aftermath of 9/11. He also applies his tools to his own life, for example in his decision to take a more active role in the struggle against racism, “challenging myself and my white colleagues to look at systemic racism and find ways to teach resilience as a resource in that struggle.” (I was honored to find references to my work for racial healing and equity and some quotes from my book Trustbuilding: An Honest Conversation on Race, Reconciliation, and Responsibility)

Both the Dalai Lama and the archbishop share Flanagan’s perspective that resilience can be cultivated as a skill. So much depends on where we put our attention. Instead of focusing on events and circumstances over which we have no control, we can reframe our situation through the choices we make.