For those of us who are appalled at the widespread support – even among so-called Christians – for a presidential candidate who has been convicted of financial fraud and sexual abuse, a habitual liar without any moral boundaries who encouraged attempts to overturn a national election, I find it encouraging to recall the words of my father-in-law, the pastor and playwright Alan Thornhill: “Evil always overreaches itself.” I have faith in this and believe that at some point enough people will have the courage to stand up for the truth. But current events test the limits of that faith.

So, it’s been a welcome therapy to read a new book by Virginia Senator Tim Kaine. I first met Tim in 1994 when he was a newly elected member of the city council in Richmond, Virginia. During the following decades, he served as our mayor, lieutenant governor, governor before being elected to the Senate in 2013.

While a committed Democrat, Tim is respected as a principled leader by people across the political spectrum. He is dedicated to racial justice and is a staunch supporter of efforts to heal the wounds of our racial history. As a young lawyer, he helped win one of the largest civil rights jury verdicts ever involving housing discrimination against minority neighborhoods. In 2007, while he was serving as governor, Virginia became the first state to apologize for its role in institutionalizing and defending slavery. That same year a Reconciliation Statue was unveiled at the site of the former slave market symbolizing apologies by officials from Liverpool, UK, the Republic of Benin, and Richmond for their role roles in the transatlantic triangle of the slave trade.

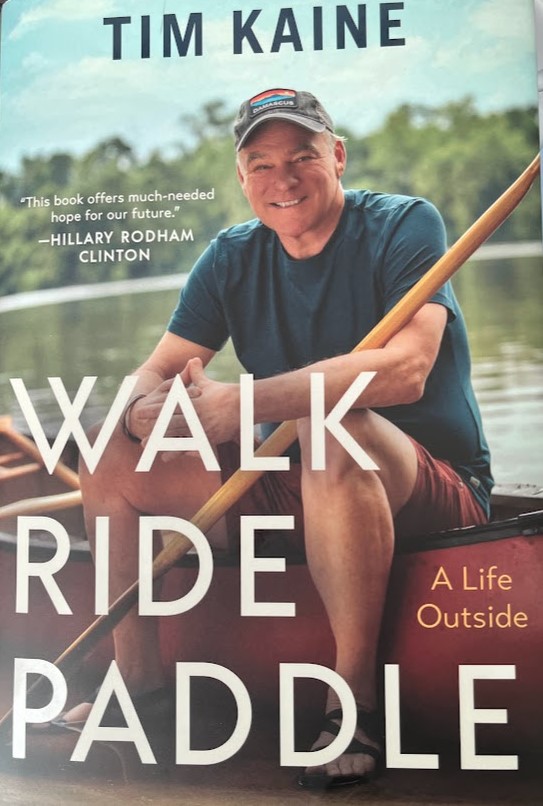

Tim’s book, Walk, Ride, Paddle: A Life Outside, comes at a time when we desperately need voices of moral integrity. It’s based on his daily journal of a 1200-mile journey over the course of two years, 2019-21, as he walks the Virginia section of the Appalachian Trail, bikes the Blue Ridge Parkway and Skyline Dive, and canoes the length of the James River. It’s a delight to read and makes me quite homesick for the state where we lived for four decades before moving to Texas. The journal includes reflections on the natural environment as well as on family, friendship, politics, racial and economic progress in Virginia, the state of the country, and his own faith and life experience. His wife, Anne Holton (an impressive woman in her own right who served as Virginia Secretary of Education), as well as some of his children, join for stretches of the adventures and he has a range of lifelong friends who come to give support. But much of the time he is alone with time to reflect on 25 years of public service.

A key moment in his life was the year he spent as a Harvard Law School student volunteering with Jesuit missionaries in Honduras. They worked in rural areas with very poor people who sometimes showed remarkable generosity. On one occasion, he found it difficult to accept a gift of food from a family whose children were clearly malnourished. His mentor, Father Patricio, told him, “Tim, you have to be very humble to accept a gift of food from a family so very poor.” He never forgot those words and has drawn two lessons from it: “First, you must be humble because you don’t have it all. You have been helped – are being helped – by others throughout your life. This help comes from obvious sources but also from completely surprising sources. Some of your help comes from people you never even know to acknowledge. You’d better be open to receiving help and acknowledging that you stand in need of help. And second, everyone has something to give to another. That, indeed, is the essence of humanity. Denying someone else’s gift – or their giftedness – for any reason is to deny the one thing that makes us human. I think of those two lessons every day of my life.”

He writes: “It was my time in Honduras that reconnected me with the person of Jesus. I came to see that his life and message are transformative; perfect and so profound that one will always find new dimensions to it. The two linked promises that that will always make Jesus relevant to mankind are the continuous availability of forgiveness plus the promise that worldly success is not the guarantor of happiness or salvation…. In Honduras I came to understand that even our mammoth human capacity to screw up the message of Jesus, so often used as a divider of people rather than an elevator of people, cannot subtract from its power.”

Wow! I never anticipated that a diary of outdoor adventures (which it certainly is) would also turn out to be such a powerful expression of personal faith. I was also fascinated by how he describes the power of walking as he starts out each day, open to facing new physical challenges and discovering new truths. He draws inspiration from a variety of sources: “God bless the Ground! I shall walk softly there. And learn by going where I have to go.” (Theodore Roethke) “I am a slow walker, but I never walk back.” (Abraham Lincoln) “Every man must decide whether he will walk in the light of creative altruism or in the darkness of destructive selfishness.” (Martin Luther King, Jr.) “Walk cheerfully over the earth, answering that of God in everyone.” (George Fox) He notes that in Honduras, one of the highest compliments you could pay someone was to remark that they were andando con la gente – walking with the people.

In many ways for me the book sums up Tim’s key qualities as a leader: openness to learning from others, freedom from ego, clarity of purpose and strength of faith.

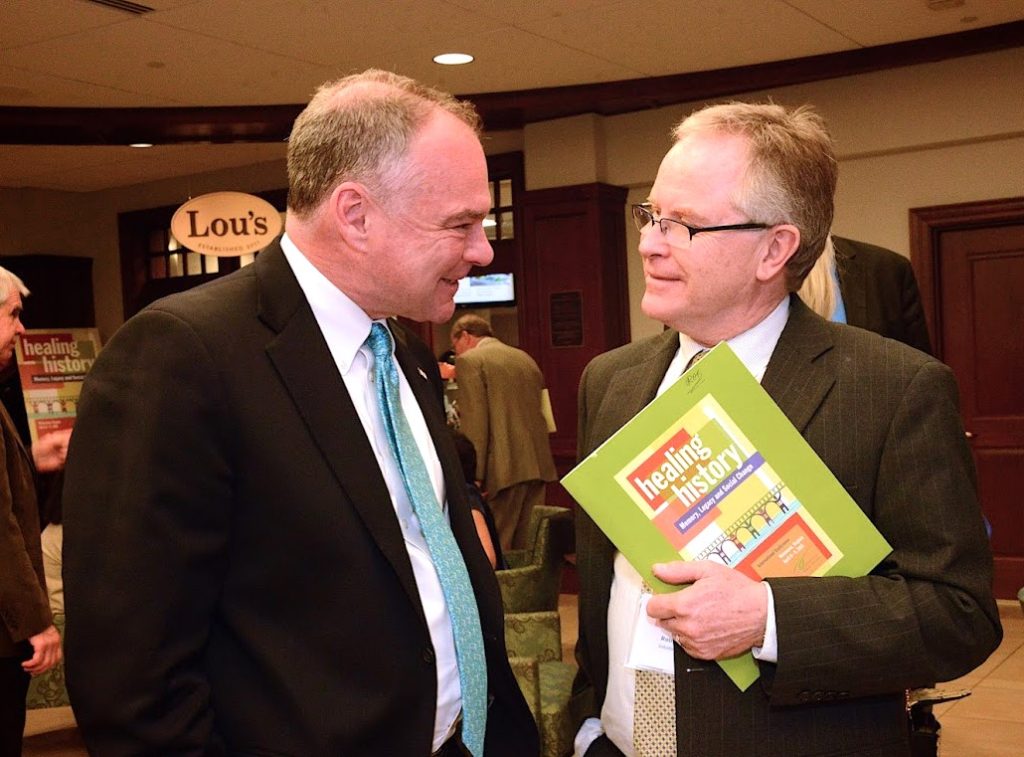

My wife and I came to Richmond just a few years before Tim, and during our forty years there he was a constant and always accessible support for our work with the Hope in the Cities team that focused on honest conversation on race, reconciliation and responsibility. In 1998, he was elected mayor by a majority Black city council. That same year he spoke at our national workshop, paying tribute to African Americans for leading the way in the region by breaking out of race-based politics. He went on to say, “This is the most important work that we are doing in the city – the work that Hope in the Cities does.” In March of 2010, when he was chair of the Democratic National Committee, he spoke at the launch of my book Trustbuilding. He said: “Hope in the Cities focuses on the ‘still small voice’, not loud and flashy approaches, or neon signs…. Listening is a lost art in this world. Hope in the Cities is creating a space where people can talk…That listening thing is needed more than ever, and not just in racial issues.”

Looking back at the past decade, Tim writes, “In 2010, we were entering the second year of the Obama administration, a high-water mark in America toward the realization of our equality project. If you had told me that Donald Trump would be president as we closed the decade, I would have laughed out loud.” Yet in 2020, he found himself voting at Trump’s impeachment trial. Afterwards, he spoke on the Senate floor to explain his vote to convict in words that he says now seem scary and prescient: “Unchallenged evil spreads like a virus. We have allowed a toxic president to infect the Senate and warp its behavior…I will not be part of this continued degradation of public trust.”

His “walk, ride and paddle” was interrupted regularly with returns to Washington for Senate duties and for meetings with constituents in Virginia. These two years also encompassed the height of the COVIC epidemic (he himself fell victim to the virus and still has some long-term effects), the violent assault on the nation’s capital, and nation-wide protests following the killing of an unarmed Black man by police in Minneapolis.

In his concluding reflections, he writes: “When I started this journey, I didn’t know that I needed emotional and spiritual refuge in the tumult of the day; that I needed to find in the timeless cycles of nature an antidote to the daily news cycles of politics, and that I needed to connect to a deeper sense of our nation’s beauty to counter my sadness over its recently polarized ugliness; that I needed to look anew at the relationships that really matter to me and devote more time to them…that I needed to think about the arc of my own life and realize emotionally what I have always know intellectually – that a title is temporary and public office is a wonderful chapter of my life, but not my life itself; that I needed to root my daily life in things that last.”

Thank you, Tim, for sharing this journey with your readers, and for all that you continue to do to demonstrate the power of a life of service, long-term relationships, humility and faith. As you say, “The work of caring for others is never finished.”