At this time of intense political and social polarization when constructive change seems a distant hope, I find myself reflecting on experiences in Richmond, Virginia. In 1980, when my wife and I became new residents of this former center of the interstate domestic slave trade and capital of the Confederacy, we found a city in transition and turmoil. The first Black majority had recently won election to the City Council and was meeting fierce resistance from the white establishment. When our Initiatives of Change team launched the Hope in the Cities program a few years later aimed at healing community divisions, it was clear, in the words of our former mayor, governor and now senator Tim Kaine, that we were “facing huge obstacles…The city government and the city in general were starkly divided along racial lines and congenitally resistant to change of any kind.”*

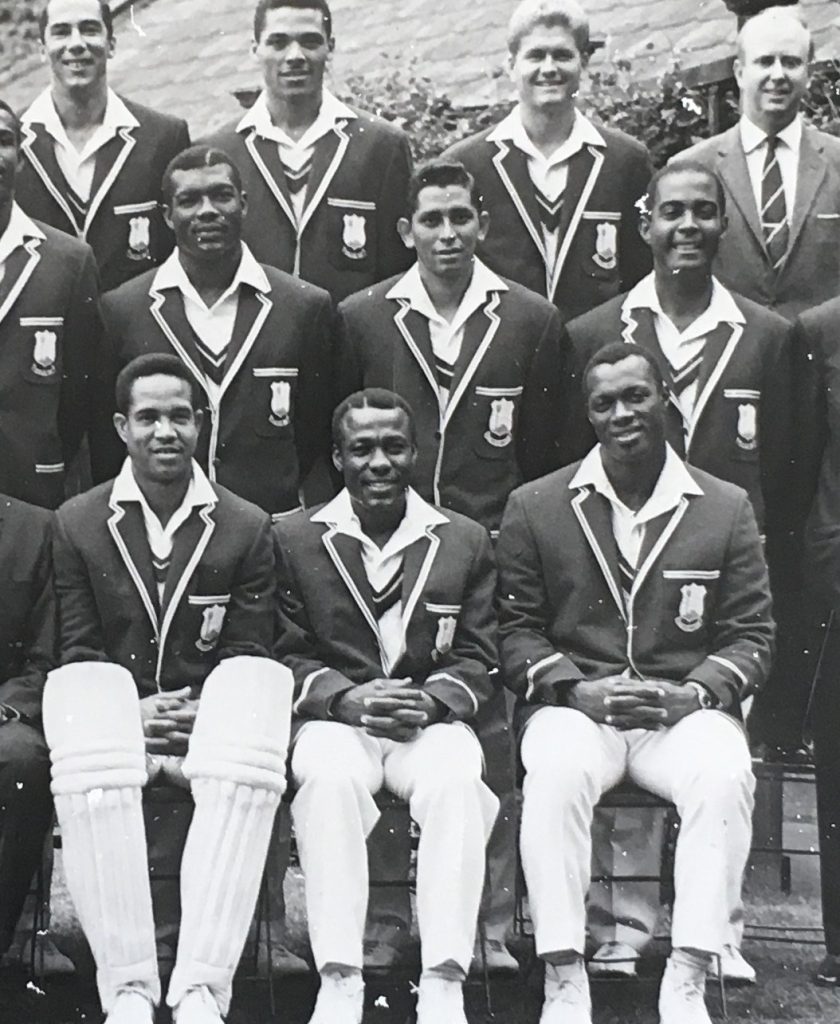

In this contentious environment, we found that international visitors helped to bring fresh and unexpected perspectives. One of them was Conrad Hunte, the former vice captain of the world champion West Indies cricket team. At the height of his fame he had set aside his career to devote his energies to preventing a race war Britain. He asked us, “Who are the six Blacks and six whites who, if they had a Damascus Road experience, could transform Richmond?” As a lay preacher, Hunte tended to frame his thoughts in biblical terms. But as I write in my book Trustbuilding, “his question illustrated a practical strategy for community mobilization… that involved careful discernment to identify individuals through whose radical change the wider community might glimpse a vision of entirely new possibilities. These individuals were not limited to the ‘usual suspects;’ they might even appear to represent ‘the problem.’”

Visits by Hunte and others gave new perspectives to those of us working to break through entrenched attitudes. And many individuals of vastly different backgrounds and opposing viewpoints did experience radical change in their lives, overcoming prejudice, fear, and deep hurts, and finding new purpose and a shared vision for the city.

A Black community organizer reached out to a white city manager with whom he had clashed publicly; the change in these two individuals and their new relationship created ripples across the city. A conservative white banker became actively involved in interracial dialogue and was willing to challenge his peers even at the risk of losing friendships. A Black preacher built a friendship with the leader of Sons of Confederate Veterans. A white member of the establishment described the “bolt of lightning” in her heart when she heard a Black American speak of the pain of racism and she recognized her own arrogance and difference. She began to open her home for interracial gatherings. Over time, this grassroots movement gained the notice and support of leaders of government, universities, corporations, museums, and faith organizations. Many of them partnered with us in hosting public events.

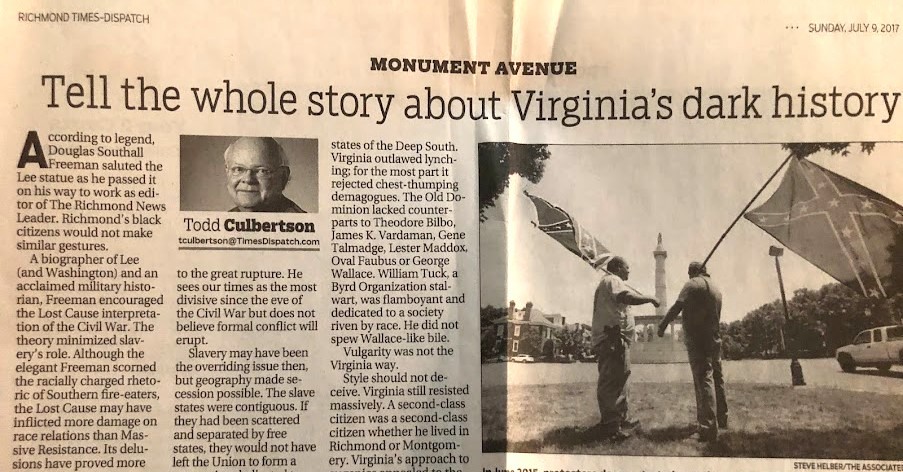

Some institutions began to shift their stance when they were invited into dialogue without accusation. The editors of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, which had been notorious for its racial prejudice, were surprised to be approached as potential allies in communicating Richmond’s potential to become a leader in healing for the nation. In the following years the paper significantly changed the tone of its news coverage and editorials, even declaring in 2015 that Virginia should take the lead in a national truth and reconciliation commission. I recall sitting in the office of Todd Culbertson, the editorial page editor, and exclaiming. “I can’t believe I’m in the office of the Times-Dispatch having a conversation about reparations!”

Recently, I have been reflecting on a question: Are there one or two individuals among the current administration in Washington who might experience a change of heart and gain a compassionate and inclusive vision for our diverse communities? I’ve been thinking about JD Vance. To many people he may represent the enemy. But unlike most of those surrounding Trump, he grew up in poverty. He knows the reality of life in forgotten parts of America. He understands the needs that ordinary people face every day. He has the capacity to do great things for this country.

After all, who could have predicted that Lyndon Johnson, a Texan, would be the president to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965? Leaders of the civil rights movement deeply distrusted him. As his biographer Robert Caro wrote in a 2008 commentary, Johnson had been such a successful strategist against civil rights that he was seen as “the young hope of the elderly Southern senators in their desperate battle to maintain racial segregation.” During his first 20 years in the House and Senate, he had voted against every civil rights bill – even bills aimed at ending lynching. However, Caro, notes, some of those close to Johnson knew there was another side to him. They often heard him speak passionately about his experience as a 21-year-old teaching the Mexican American children of impoverished migrant workers in the little town of Cotulla.

Jesus often chose the “wrong people.” A tax collector. Humble fishermen. A woman of doubtful repute. Hardly the usual material to generate a spiritual and social revolution. In this Easter season, rather than spending energy venting my frustration at Washington, I am praying every day that one or two unexpected people may have a Damascus Road experience.

*From Tim Kaine’s foreword to Rob Corcoran’s book Trustbuilding: An Honest Conversation on Race, Reconciliation, and Responsibility (University of Virginia Press, 2010)