In the summer of 2002 Rev. Syngman Rhee addressed an international conference in Caux, Switzerland. Perched high above Lake Geneva, Caux Palace has offered a place of healing for bitterly divided groups – beginning with French and Germans after World War II. As he approached the podium, the Korean-born peacebuilder and respected leader of the Presbyterian church (USA), removed his shoes. He explained “I am deeply honored to be on this ‘holy ground’ at Caux where so many people have dedicated their lives to reconciliation, peace and justice for all humankind throughout the world.”

My colleague Paige Chargois, an African American pastor who had invited Rhee to Caux, rose from her seat, and placed her own shoes at the foot of the platform. Many others of us followed suit until there was an array of dozens of shoes of all shapes, sizes and colors.

As Paige commented to me, “Of course, for Rev. Rhee, it was a flash back to the biblical instruction that God gave to Moses, who was just out leading the sheep to pasture, as he approached Mt. Horeb. He knew full well at Caux it was “A God-Moment” which he invited us into and transformed for all of us.”

Some years later in Caux I welcomed another peacebuilder, Gail Christopher, the senior vice president of the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. It was her vision that launched Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation in cities across America. She had invited twenty leaders of US organizations working for racial healing and equity to join her in Caux. After I took her to her room, she asked me to show her around the building and the grounds. We walked through the Great Hall and then strolled along the terrace overlooking the lake. As we walked and talked Gail said, “I feel this is a place where healing can take place.”

Caux is a unique place. But we can all create spaces where healing can occur. Sometimes it may mean simply opening our home or our heart. When the first Black majority was elected to the city council of Richmond, Virginia in 1977, Helen Rumple a retired white secretary, invited one of the new councilmen, Walter Kenney, and his wife, to her home for tea. It was the first white home Kenney had been invited to in the former capital of the Confederate states. In 1993, as mayor of Richmond, he invited the international community to join in the first walk through the city’s racial history.

Soon after the September 11 terrorist attack in 2001, two other Richmonders, Ben and Virginia Brinton, decided to reach out to Muslims. They joined the local Interfaith Council. At the first dinner event, Virginia prayed, “Lord, if you want us to get to know some Muslims, please arrange for us to have dinner with some.” That evening they met Malik Khan, the president of the Islamic center, and his wife, Annette. The two couples became firm friends. They were able to have honest conversation and to hear each other’s stories. Virginia said, “God gave me the courage and conviction to leave my comfort zone and get to know new people. In my talks with Muslims, I realize they too feel the need to reach out and come out of their seclusion. It has been a superb learning experience for us.”

Twenty Catholic and Protestant representatives of local government, education, agriculture, business and the voluntary sector from Northern Ireland spent a week in Richmond in September 2006 to study the city’s approach to reconciliation. They remarked on the power of physical contact when they were asked to link hands and walk silently in single file along the historic trail of Enslaved Africans. In this walk through history, “one community was allowed to face its pain, and the other its shame,” they said.

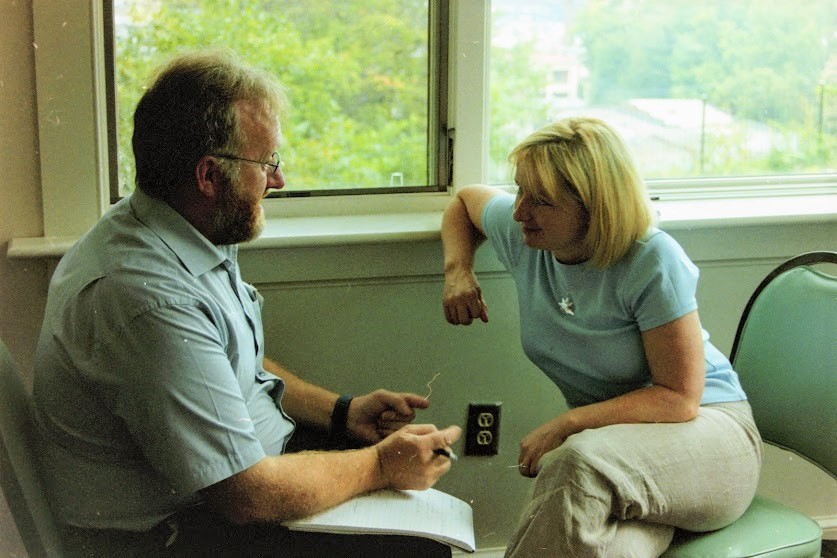

Later, we asked the group to divide into pairs. Each person was asked to outline briefly a situation where he or she was in conflict with another family member and then attempt to describe that conflict from the viewpoint of the other person. We then repeated the exercise around their experiences of sectarian division.

For many, the experience was hard at first. “By telling the other side’s story it was as if I was letting my side down and giving credence to the other side’s beliefs,” reported one woman. “I felt guilty, disloyal to my group,” said another participant. But several also remarked on the feeling of responsibility of trying to tell the other side: “You begin to doubt. Have I got this right?”

“I felt liberated from fear of the unknown,” said a young man from Belfast. “Sometimes, when you think about the other side and express it, you exorcise your demons. You are liberating yourself. It’s more than tolerating; it’s respecting, not necessarily agreeing.”

The tagline of this website is “creating a space for change.” In our trustbuilding work with Initiatives of Change we often say that each person has a sacred story, a narrative that is precious to them. Listening to that story, however difficult or painful is an act of hospitality. When we step into another person’s life or home, or when we invite them into ours; when we engage with them in conversation of the heart, we are entering their sacred space or welcoming them into ours.

Like Syngman Rhee, we enter sacred spaces humbly, taking off our shoes, leaving our assumptions, our opinions, our prejudices and our pride at the door. We open our minds and our hearts to what may be revealed. In these sacred spaces, trust may be built and change may become possible.