Across the country, interest in anti-racism has exploded. Books such as How to be an Anti-Racist, White Fragility, and Caste have topped the non-fiction best seller list. Large numbers of white Americans are better informed than ever. Faith communities are engaging in deep conversation about their history and their responsibility. Numerous groups offer training. Corporations constantly use themes of diversity and inclusion in their marketing.

However, as some commentators have noted, white liberals often appear more eager to learn about race through books or workshops than to make changes in their own lives that might infringe on their areas of privilege. Is it possible that the biggest obstacle to racial equity is white liberals who resist risking these privileges and who focus more on performative anti-racism and cultural battles? Slogans are easy; living in ways that move our communities towards equity is hard.

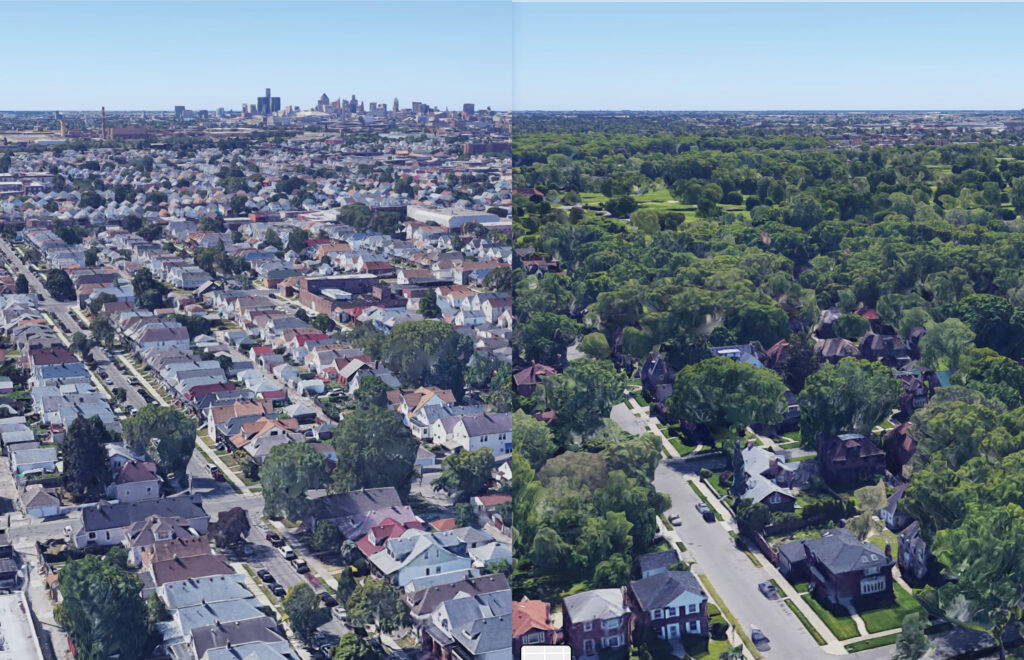

It is a striking fact that the most liberal cities in America are often the most segregated by race and economic class. Austin, Texas, where I live, takes pride in its image as a progressive city, but as an African American professor commented to me, “The trouble with Austin is that it believes its own PR.” Black Lives Matter and other signs embracing diversity adorn tree-lined streets where neighbors of color are conspicuously absent. The relentless pace of gentrification with astronomical house prices pushing up property taxes (Texas has no income tax) makes the city increasingly unlivable for anyone on a modest income. A recent referendum resulted in a ban on camping in public places by our homeless population, but there is a severe scarcity of affordable housing.

Education is one area where white privilege is dramatically evident. The columnist Nicholas Kristof notes that the United States “embraces a public education system based on local financing that ensures that poor kids go to poor schools and rich kids to rich schools.” He writes that educated white Americans are repulsed at the history of separate and unequal drinking fountains for Black Americans, “but seem comfortable with a Jim Crow financing system resulting in unequal schools for Black children — even though schools are far more consequential than water fountains. Perhaps that’s because we and our children have a stake in this unequal system.”

My friend Stephanie Hawley is Austin’s first racial equity officer for its public schools. Her first report highlighted the lack of community input especially by Black and Latino parents and the “powerful impact of white families with agency and social capital” on issues such as school closures and redistricting. She comments, “This is what 21st century racism looks like.”

In most American cities, zoning laws prohibit the construction of more affordable homes such as duplexes and larger multifamily units. Single-family exclusive zoning has become known as the “new redlining.” As Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation who focuses on segregation in schools and housing writes, restrictive zoning laws apply to three-quarters of residential land in this country. So “wealthy white Americans benefit from single-family zoning laws in the suburbs around those fine ‘public’ schools. The effect of this zoning is to freeze out low-income families and keep neighborhoods more segregated.” He points out that the most restrictive zoning is found in politically liberal cities, where racial views are more progressive. Many of those who benefit from this would be appalled at any suggestion of racism. But as Harvard’s Michael Sandel notes, social psychologists have found that highly-educated elites “may denounce racism and sexism but are unapologetic about their negative attitudes toward the less educated.” While Black-white residential segregation has declined by 25 percent since 1970, income segregation has more than doubled.

A disconnect

There also appears to be a growing disconnect between progressive activists and many rank-and-file Black and Latino voters. The liberal flank of the Democratic party is far whiter than in earlier years. White liberals are significantly further to the left on cultural issues than Black and Latinos who tend to be more moderate in their views and are less supportive of identity politics around sexuality and gender. Religion is still a big factor for many Blacks. Latinos value family life. Both are concerned about basic issues of employment, housing, health care and safety. It seems clear that in places like Texas, Democrats lost votes among Latinos and African Americans in the 2020 presidential elections because of this disconnect.

Virginia’s governor Northam survived a blackface scandal from his youth with the help of Black Democrats who saw a chance for policy concessions. Progressives called for his immediate resignation. Black political leaders and the majority of Black voters decided to give him a second chance. As the New York Times reported, “Both got more from the relationship than they could have imagined.” Northam and the Black leaders who supported him “showed the power of redemption, humility and growth.” He is “set to leave office with another legacy: becoming the most racially progressive governor in the state’s history, whose focus on uplifting Black communities since the 2019 scandal will have a tangible and lasting effect.”

In his campaign to win the New York City Democratic primary for New York City mayor, Eric Adams, an African America, said progressive slogans and policies (such as “defund the police), threatened the lives of “Black and brown babies” and were being pushed by “a lot of young, white, affluent people.” Columnist Thomas Edsall observes, “Black folks don’t feel the same motivation to save face or protect some image of self that white liberals are struggling with. So black folks can be honest about these questions in ways that white liberals can’t because they’re too busy worrying about wokeness scores.”

What might we white liberals do differently that would help to build increased unity with rank-and file minority voters and blue-collar workers, and might even begin a constructive dialogue with other whites who are more conservative but whose participation is necessary to achieve systemic reform? Here are a few suggestions:

Be aware of selective empathy. It’s easy to empathize with some people: those we feel comfortable with, those we approve of, or whose political views we share, or who appear to be victims. It’s much harder – but just as necessary – to open our hearts and minds to people or groups who we perceive as “the problem” or people of different political views. We need to be willing to move out of our comfort zones.

Listen more and preach less. Roger Cohen writes: “To win, liberals have to touch people’s emotions rather than give earnest sermons.” Another commentator says that liberals need to find a way to connect with the lives of people, particularly in small towns of the post-industrial wasteland whose traditional culture has been torn away. This will require careful listening to the hopes and fears of people with whom they may feel deeply opposed.

Be a supportive presence. There is great value in simply showing up without any need for a formal role or recognition. Resist the impulse to try and take control. When white parents “discovered” our excellent majority black neighborhood school in Richmond, Virginia, they brought so many “helpful” ideas that the principal said it felt like a hostile take over.

Create a welcoming environment for honest story-sharing. Learn to listen to stories without judgment. David Brooks writes: “The collapse of trust, the rise of animosity – these are emotional, not intellectual problems. The real problem is in our system of producing shared stories. If a country can’t tell narratives in which everybody finds an honorable place, then righteous rage will drive people toward tribal narratives that tear us apart.”

Go beyond performative anti-racism and be open to making uncomfortable personal changes. This might include supporting a rise in taxes (not property taxes) to support education or legislation to remove restrictive zoning laws. It might mean welcoming shelters and housing for low-income people in our own neighborhoods. It might mean having honest conversation around school redistricting or being willing for our children to be a minority in a school. In an earlier blog I wrote about a question we posed to the Richmond community: “If every child were my child, what might I do differently?”

Connect inner change with outer change. In recent decades, liberals have contributed to an acceptance of relative morality that has been particularly costly for those at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder where the collapse of the working-class family is a central contributor to growing inequality. We have been reluctant to hold ourselves and others accountable. We must recognize the need for a moral and spiritual transformation in the lives of individuals as a foundation for sustainable systems change.