Little is known about the remarkable woman whose resilience and determination resulted in Richmond’s most notorious slave jail becoming the birthplace of today’s Virginia Union University. Yet Kristen Green, through meticulous research and vivid imagination, has illuminated the story of Mary Lumpkin and placed her in the context of the struggle for freedom and dignity in America’s brutal environment of chattel slavery.

The Devil’s Half Acre paints a stark picture of the lives of the two million women and girls like Mary who were enslaved in the American South in the decades before the Civil War. After the United States banned the importation of enslaved people from Africa in 1807, the slave trade changed from international to domestic trafficking. Over the next decades, about one million men, women and children were “sold down the river” from states such as Virginia to meet “the insatiable demand for free labor in the cotton and sugar fields in the Lower South.”

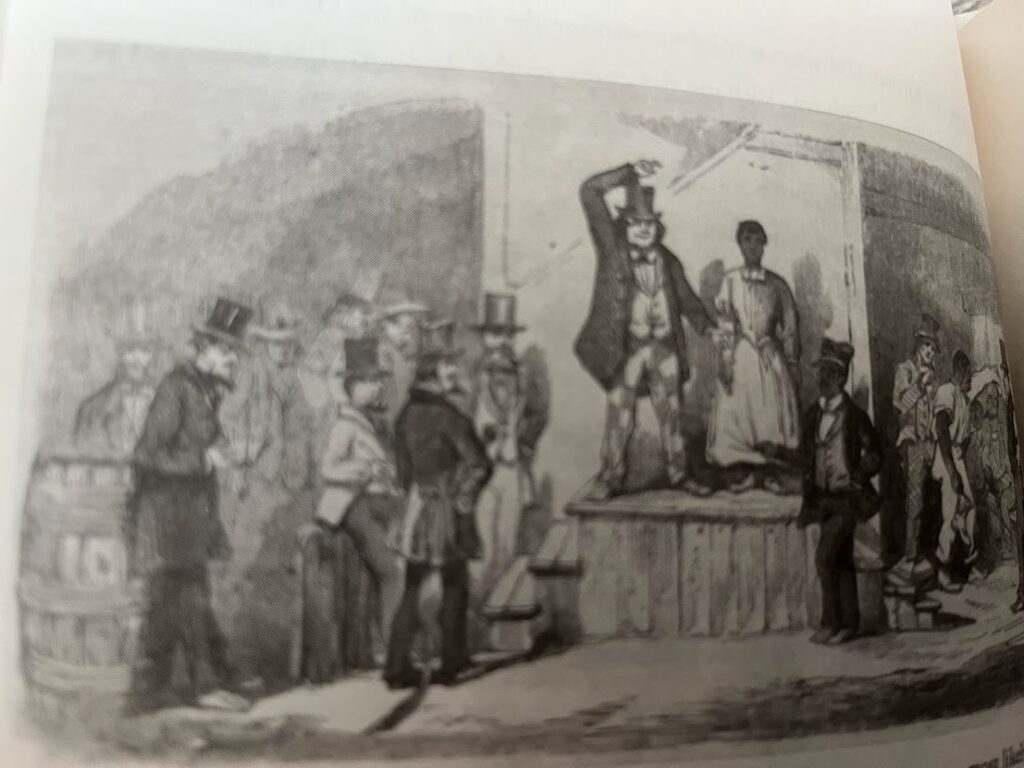

Richmond became an epicenter of this interstate commerce in human beings. The forced resettlement, reports Green, was twenty times larger than the Native American removal campaign of the 1830s, bigger than the immigration of 500,00 Jews who arrived from Russia and Eastern Europe in the 19th century, and bigger than the wagon-train migration to the West. Prices for enslaved people doubled between 1800 to 1860. More than 120,000 people were sold from Virginia to southern states in the 1830s, and by the 1840s Virginia was responsible for shipping nearly half of all the enslaved people who were taken across state lines. In 1857, sales of enslaved people in Richmond totaled $4 million annually, about $440 million in today’s dollars. Enslaved people were often used as collateral for enslavers who wanted to borrow money. Thomas Jefferson mortgaged 150 people in order to build Monticello.

It’s hard to overstate the cruelty of the system. Young girls and boys as young as two years old were torn from their mothers. Rape was an everyday hazard for Black women and girls from the moment they were brought to America. Some arrived already pregnant after the horrendous Atlantic crossing. (One analysis of DNA results indicates that the average self-identifying Black American today has a genetic make-up that is 24 percent European. About 4 percent of “white” Americans carry African blood; in South Carolina and Louisiana it is 12 percent.) “Enslavers found they could get the sexual fulfilment they desired while at the same time expanding the population they enslaved in the form of their own children.” While white society imposed lethal penalties on Blacks associating with white women, white men were free to do as they chose. “White women were skilled at denial even when the multiracial children under their roofs resembled their own,” writes Green.

The rapidly growing multiracial population presented a problem for the early settlers. Should a child resulting from rape or coerced sex be free or enslaved? Whites needed enslaved people to work in the fields, so in 1662 Virginia ruled that children born to enslaved women would also be enslaved.

This was the world into which Mary Lumpkin was born. She was fair-skinned; her mother had been forced to bear the child of her enslaver. She was bought as a young girl by Robert Lumpkin who became one of Richmond’s most notorious and wealthy slave traders. By the age of 13 she had born his first child. Over the years she was to bear four more.

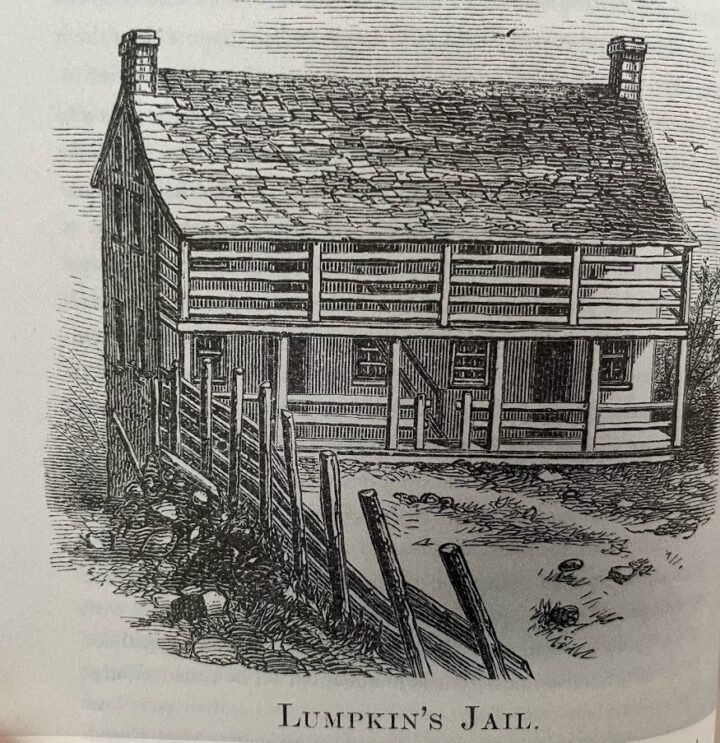

Lumpkin owned a property in downtown Richmond which functioned both as a boarding house for traders and a jail for holding enslaved people – often those who had been captured after attempting to escape. Numerous other slave traders operated in the area known as Shockoe Bottom where people were bought and sold on auction blocks. Over the years Lumpkin held thousands of people in his jail. He and his employees would torture and beat them. The compound earned the title of “The Devil’s Half Acre.” The most famous occupant of the jail was Anthony Burns who stowed away on a boat to Boston while working on Richmond’s waterfront. In Boston he was arrested and tried under the Fugitive Slave Act and returned to Richmond. The trial made national news. He was held and tortured in Lumpkin’s Jail, where he interacted with Mary.

The complexity of history

Mary was in a strange position. She was likely separated from other enslaved people and given some freedom. As well as looking after her children, she likely took care of Lumpkin’s household and managed the boarding house. Over time, she assumed the role of Lumpkin’s wife – although they could not legally marry – and even took his name.

What shines through this story is the courage and the determination of Mary Lumpkin, and women like her, to protect and educate their children. Mary was literate and left a few letters for posterity. Like others in her position with prominent ensalvers, she negotiated with Robert Lumpkin, and extracted promises of freedom for her children. Some enslavers were eager to protect their children from being captured or enslaved by others, so they facilitated a steady stream of multiracial families to places such as Philadelphia where Quaker’s were strong advocates for abolition and to Ohio. Many of these children were ultimately freed by their enslavers. Two of Mary’s daughters attended a seminary in Ipswich, Massachusetts, and Robert Lumpkin enabled Mary to purchase a home in Philadelphia where she and some of her children lived in a neighborhood populated by freed Blacks.

Green’s history illustrates the complexity of history. We will never know how the children of Mary and Robert Lumpkin felt about their father. All of them “passed” as white and all of them ultimately changed their names. Yet after the Civil War, Mary returned to Richmond, the place of her enslavement, and acted as manager for the former jail which had been converted into a hotel. At his death, soon after the war, Robert Lumpkin left all his property to her.

God’s half acre

In 1866, Nathaniel Colver, a white abolitionist, and former minister, was looking for a building in Richmond where he could house a school for freed African Americans. White property owners refused to sell any land. Then one day after fasting and praying he came across a group of Black women on the street. Mary Lumpkin was among them. “In the midst of the group was a large, fair-faced woman, nearly white, who said she had a place which she thought I could have.” He agreed to rent the former jail for $1000 a year. Green writes, “the building that had been an epicenter of pain and suffering for so many would take on a new life as a place of Black education.”

Soon, eager students were studying reading, grammar, math, and geography. Some classes were held in former jail cells and former whipping posts became lecterns for professors. One contemporary wrote, “It was no longer the devil’s half acre but God’s half acre.” A few years later, the school moved to a new location as the Colver Institute; in 1876 the Virginia General Assembly incorporated the school as the Richmond Institute; and in 1899 it was reincorporated as Virginia Union University, one of the oldest historically Black colleges and universities in America.

Uncovering history

Until 1993, there had been virtually no public conversation about Richmond’s history of slavery. The breakthrough came with an event that year not mentioned in Green’s account. An international conference hosted by Hope in the Cities (a program inspired by the nonprofit Initiatives of Change), the City of Richmond, and Richmond Hill ecumenical retreat center, featured the first public “walk” to acknowledge the sacred land of Native Americans, the city’s history of human trafficking, and the enormous loss of life in the Civil War. A “slave trail” retraced the footsteps of captured Africans from the James River to the site of the former slave market. This history had been conveniently “forgotten” but Nancy Jo Taylor, a Black school teacher, had long been aware of several key sites. The following year, Mayor Walter Kenney created a Unity Walk Commission to develop the trail. I was privileged to serve on the commission for ten years along with two of the visionaries of the original walk, Rev. Benjamin P. Campbell of Richmond Hill and my colleague Dr. Paige Chargois. Key players over the years included James River Park manager Ralph White who organized the first signage, recruited volunteers to clear the trail and build footbridges, Janine Bell of the Elegba Folklore Society, Rev. Sylvester “Tee” Turner of Hope in the Cities, and Dr Philip Schwarz of Virginia Commonwealth University who provided invaluable historical research. In 1998 the Slave Trail Commission was formally established based on the existing commission. When Virginia delegate Delores McQuinn joined the commision she gave indefatigable leadership to the effort to tell the story of Lumpkin’s Jail.

As Green reports, for decades the commission and many others in the Richmond community have worked persistently through frustrating delays for proper recognition of the site. In 2007, a Reconciliation statue memorializing the transatlantic British, African and American slave route was unveiled nearby, and that same year Governor Tim Kaine led the General Assembly in voting to express profound regret for Virginia‘s role in the slave trade and for the exploitation of Indigenous people. In 2008, the city awarded a contract to Matthew Laird to conduct the first full archeological dig which uncovered the footprint of the Lumpkin’s Jail. I vividly recall a 2016 event when Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, sat with his Republican predecessor Bob McDonnell who had pledged state support, as Mayor Dwight Jones announced the hiring of the Smith Group to design a museum and heritage site. Progress has sometimes been been agonizingly slow, but in 2022 the city council voted to establish a foundation to fundraise for a National Slavery Museum.

Mary Lumpkin led the final years of her life in New Richmond, Ohio, a settlement for many freed Blacks. Her grave is unmarked. Thanks to Kristen Green, her story can take its place as an essential part of Richmond’s history. The site of the jail where she was imprisoned can become a place of truth-telling, a symbol of hope, and a challenge to build a future of justice for all.

The Devils Half Acre: the Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated the South’s Most Notorious Slave Jail, Seal Press, 2022. Kristen Green is a reporter and the author of Something Must be Done About Prince Edward County