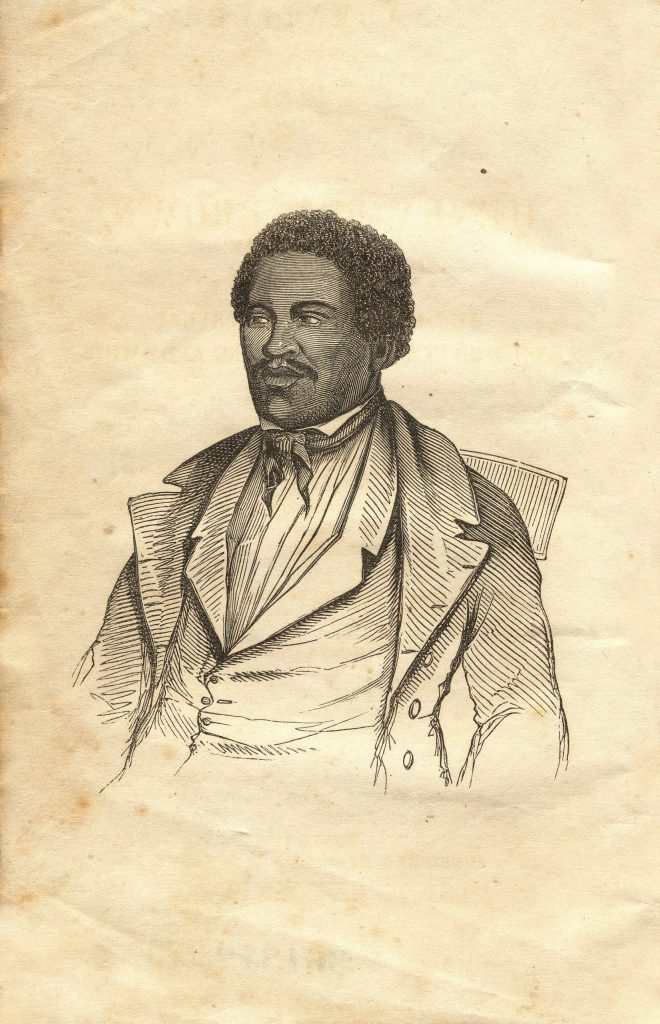

In 1849, Henry Brown escaped from slavery in Richmond, Virginia, by arranging to have himself mailed in a crate to Philadelphia. Henry “Box” Brown as he became known, was among some fifty-five men owned by William Barret who had sold Brown’s pregnant wife and child to another slave master. Most of the men worked in Barret’s tobacco factory.

Brown’s story features in the opening chapter of Christopher Graham’s book, Faith, Race, and the Lost Cause: Confessions of a Southern Church. Graham has delved deep into vestry records and drawn on multiple other sources to compile this remarkable historical analysis of racial attitudes in the 170 years of St Paul’s Episcopal church. For a century after the American Civil War, it became known as the “church of the Confederacy,” honoring the memory of Jefferson Davis, the president of the rebel Confederate states, and General Robert E. Lee who led the army fighting to preserve a system of slavery. Both men worshipped at St Paul’s. Yet over the past decades, the church has become known for its interracial efforts for healing and for taking steps to repair the legacy of a racist past. Graham explores this surprising evolution.

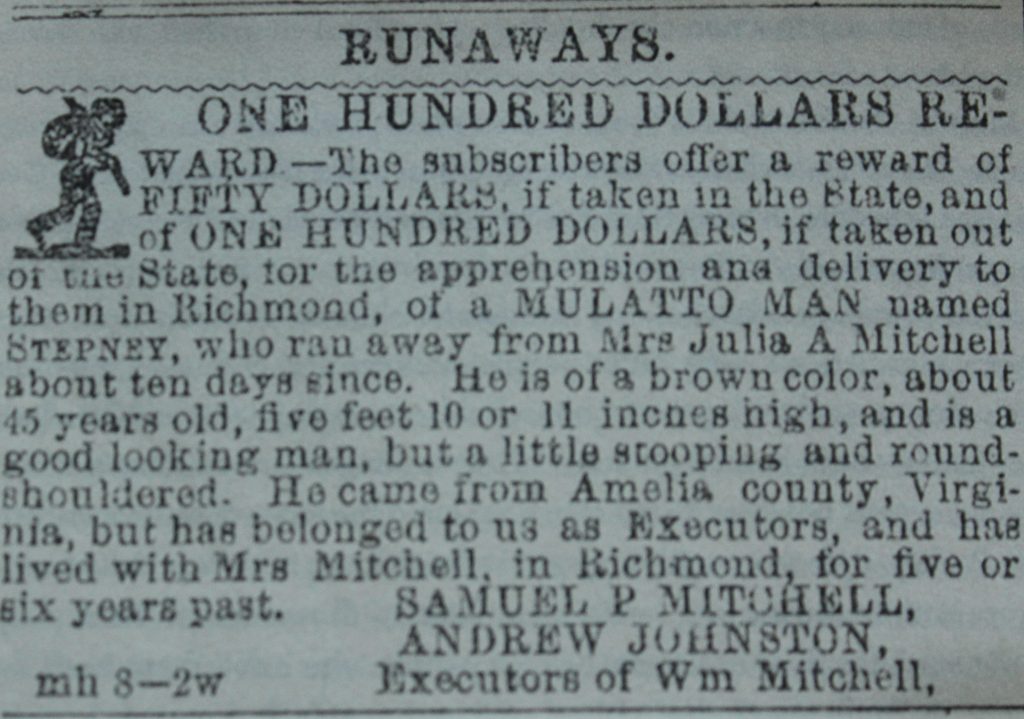

William Barret contributed to the founding of St Paul’s, and he rented a pew there. On his death his estate dedicated $50,000 to the church’s Home for Orphans. The striking irony of this act of generosity is symbolic of the contradiction that Graham highlights through the book: Apparently sincere Christians were deeply committed to a system of human bondage. St Paul’s counted among its congregation prominent members of the city’s merchant class and captains of industry who owned an average of nine people per household.

Episcopalians in Virginia, along with most Southern Protestants, believed the Bible and Christianity justified slavery. Although it may be difficult to comprehend, they also genuinely believed that it was their “sacred obligation” to “nurture and care” for the enslaved and that Black people should “happily submit to and faithfully serve” white people. As Graham writes, “It strains the credulity that they did not more readily testify to the violence, rape, family separation, and grief” that they witnessed or inflicted. Some did speak of alleviating the evils of slavery but not slavery itself. The big challenge for the reader, “may be in coming to grips with the fact that St Paul’s people always considered themselves to be acting in the best material and spiritual interests of, and with the warmest regard for, Black men and women.”

The congregation was fully invested emotionally, financially, and spiritually in the Civil War. Many fought, and some died, in the Confederate army. After the war, the congregation installed magnificent stained-glass windows as a tribute to Jefferson Davis and Lee, and to support a false narrative of former glory that depicted the South as morally virtuous and denied slavery as the primary cause of the war. St Paul’s became known as a “shrine” for “the Lost Cause.”

During the post-war Reconstruction period, huge numbers of African Americans registered to vote, securing a majority in Richmond. Pushing back against this threat to white control, “St Paul’s member and chairman of Richmond’s Conservative Party, Thomas McCance, encouraged ‘every man’ to “scrupulously police Black voter registration for any credible reason to disqualify registrants.” The 1901 Virginia Constitutional Convention purged most eligible Blacks through poll taxes and literacy tests, leading to 86 years of rule by a Democratic party dedicated to white supremacy.

St Paul’s members were frequently conflicted about their relationship with Black Christians with whom they craved a “religious and familial bond.” But the very nature of segregated society made fellowship impossible. In 1916, Mary-Cooke Branch Munford rallied whites to support the expansion of a hospital to serve African Americans. She and other Richmond liberal-minded elites, “inspired by Lost Cause tales of benevolent masters, used their social standing and wealth on behalf of the city’s Black population.” The church was often eager to improve “race relations” and promoted charitable causes but only within the context of Jim Crow segregation. Parishioners were relatively progressive in their efforts for better schools and housing but were completely blind to the fact that the problem was separation. St Paul’s members were involved in the legislation that disenfranchised most Blacks, and later in redlining that prevented them from purchasing homes in white neighborhoods, and in the decision in the 1950s to construct a highway through the heart of the thriving African American business district.

Yet starting in 1969 with Rev. John Shelby Spong, the church began a gradual transformation in its perspectives on race, racism, and racial relationships. Over the next years, members of the congregation created Housing Opportunities Made Equal (H.O.M.E) to educate and inform real estate agents to offer equitable housing, and the Richmond Urban Institute which produced a 1981 paper on racial tensions in Richmond and a study on redlining that resulted in a regulatory order to prevent illegal exclusion of all-Black neighborhoods from loans.

By the time my wife and I joined the church in 1980 (we were members for 40 years) it was building what Graham describes as a “post-Confederate identity.” The congregation under the leadership of Rev. Robert Hetherington incubated important efforts such as the Micah Initiative that inspired scores of area congregations to support elementary school children and teachers, particularly in high poverty areas, and the Richmond Hill ecumenical retreat center which has become a vital place of spiritual renewal and racial reconciliation. Members of the congregation were also instrumental in the development and support of Hope in the Cities, a program of Initiatives of Change. Indeed, Rev. Ben Campbell, the founder of Richmond Hill, was my closest ally in the early development of Hope in the Cities as we launched a campaign for honest conversation on race, reconciliation, and responsibility, starting with Richmond’s first public walk through its racial history in 1993.

Today, the congregation includes people of color in leadership positions. It actively collaborates with African American churches and is a leading ecumenical voice for interfaith partnerships and justice.

But the 2015 massacre of nine Black Christians in a South Carolina church by a young white man “infatuated with Confederate history” and racist narratives, prompted Rev. Wallace Adams-Riley to challenge the church to confront its history more directly. Confederate flag motifs and memorials to Lee and Jefferson were removed. A History and Reconciliation Committee embarked on a four-year journey of study, dialogue, forums, memorialisation, and reflection. I served on the committee along with Christopher Graham. The process was not without challenges. Some of the congregation were impatient to move beyond historical study to action. Others were pained to discover that individuals they had admired in earlier years were shown to have been staunch segregationists.

In March 2018, the church welcomed the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, the Most Rev. Michael Curry, the first African American primate of the Episcopal Church, at a public forum, “Bending toward truth: a forum on race and religion in Richmond.” Up to 500 people from across the region heard panels of historians, clergy of various denominations, the leader of a foundation focused on health, and the CEO of a museum. In a call to action, Curry told the forum, “This is important not only for Richmond but for our country, and indeed, for our whole world, for our common humanity…we cannot continue as we have been going…we must find a better way and you are modeling how we can find that better way.”

Graham says this is just the start of the journey of atonement and repair. He acknowledges the apparent slowness of the process, but he believes it was important that the congregation was fully supportive of the work in contrast with some churches that were torn apart by confronting their history. “Taking time for trust building yields results.”

He frequently highlights the power of historical narratives. “St Paul’s is a story church…it has made significant contributions to the history, literature, and public conversations about white supremacy that it has told about itself and about race in the former Confederacy” and it has a special obligation now to “redeploy the power of its historical imagination.”

Fourteen papercut art pieces now line the sanctuary. Created by Janelle Washington, “The Stations of St Paul’s” replicate the “Stations of the Cross,” but they recount stages in the church’s racial history. “In a church once known as a destination for those wishing to bask in the reflected glory of Confederate saints, it is our hope that the Stations become a more compelling draw.”

This is an honest book, written from the perspective of a white American. While being forthright about the evils of the past, Graham avoids condemnation of earlier generations. He cautions those of us who might jump too quickly to pass judgment to be aware of our own “supreme confidence in the righteousness of our causes” however morally correct, and to consider our own “blind spots.”

Christopher Graham is a historian and the Curator of Exhibitions at the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia