I sat down to write this column the day after Justin Trudeau won a second term as Canada’s prime minister. He lost the popular vote and his Liberal Party lost its majority in the House of Commons. To the surprise of many observers, the Bloc Québécois, a party that promotes Québec independence and which had appeared very weak early in the year, emerged with the third highest number of seats.

Last year, the provincial elections saw a landslide victory for the Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ), a nationalist party, which went on to pass controversial legislation known as Bill 21 which bans certain public-sector workers from wearing religious symbols such as niqabs, hijabs and turbans.

In this context, a new project being launched by Initiatives of Change Canada seems particularly timely. Earlier this month, I spent two days in Montreal meeting with a group of community leaders who are engaged in a trustbuilding program to address the province’s societal challenges. They say that “Québec is a microcosm of the country as a whole, with the added complexity of identity, nationalism, linguistic difference, undocumented immigration, religious tensions, and the long-standing history of oppression and colonization of Canada’s first peoples.” Our Canadian colleagues aim to train and equip a cohort of trustbuilding trainers and facilitators with tools and skills to bridge cultural, social and religious divides in their respective communities.

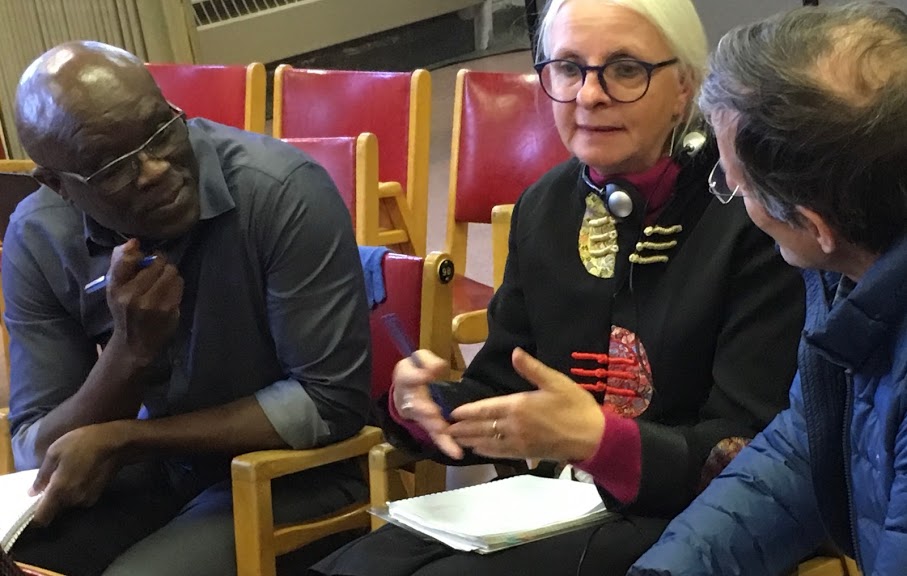

Along with Ebony Walden from Richmond, Virginia, and Roxann Kioko from Eastern Mennonite University, I took part in an information session and discussion with about 40 people from interfaith and peacebuilding organizations, academia, government, business and the arts. We outlined the ongoing trustbuilding experience in a city like Richmond, VA, with its history of slavery and segregation, and we engaged the participants in exploring the roots and fruits of distrust in Québec.

The emerging trustbuilding program builds on several decades of collaboration by IofC with like-minded partner organizations to foster honest dialogue and steps towards healing among Aboriginals, Francophones, Anglophones and immigrants. Tools for Peace is a network of community-based organizations in Montreal who work to develop peace skills within communities with the aim of preventing violence and addressing its consequences. It brings together more than a dozen organizations with various expertise in areas such as communication, conflict resolution, human rights, intervention with children and families, restorative justice, gender equity, and respect for diversity.

I talked about the significance of the trustbuilding program with its two leaders. Joseph Vumiliya is IofC’s regional coordinator for Québec. He came to Canada in 2012 after many years of work with an international NGO in sub-Saharan Africa. Joseph says, “I have experienced broken trust at a personal level as a survivor of genocide in Rwanda where I lost most of my family. I felt that IofC was already doing good work in Canada, but it was not going deep enough. This is also true for our partner organizations. In Canada – and in Québec in particular – there is a denial of racism, but in fact all the time we have examples of it. I have experienced it and some of my friends have experienced it much worse than I have. It is well rooted, and people do not want to talk about it.”

Geneviève Dick, who teaches philosophy, is the trustbuilding program manager. Her mother is a Catholic Québecoise. Her father is a Mennonite from Western Canada whose father emigrated from Russia. Geneviève says that some of her interest in philosophy stemmed from the inherent tension in her own family. She drifted away from formal faith, but when she came across writings by Frank Buchman, she was intrigued by how he connected personal and social change. Her teaching job in the north of the province put her in proximity to the indigenous population and to the mines; this gave her added insight into the social issues facing Québec.

Joseph and Geneviève believe that the program must address the interconnected issues of history, racism, and identity. Geneviève says, “A lot of French Canadians look at France as a model for exclusion and see multiculturalism as a threat. Xenophobia and racism are perceived as protecting local identity.” She is very sensitive to injustice. “Just being friends will not solve all the problems of the world. But when I took part in the trustbuilding workshop for trainers in Caux (the IofC international conference center in Switzerland) this summer, I saw that we were actually talking about structures and injustice, and how to involve everyone – not just the activists, and this answered my frustration.”

Geneviève also points to generational divides in Québec. “For example, many older people support Bill 21 and are against any religious symbols in the public space. Younger people don’t understand the issue because they are totally secularized and don’t see the difference between a hijab and a tattoo.” She adds that many of her generation are focused on the environment, “but this group tends to be very white and often doesn’t pay attention to indigenous issues.”

She and Joseph remarked that the presence of outsiders like Ebony, Roxann and me at the discussion enabled participants to hear truths in a new way, sometimes from people with whom they were already working and thought they knew. “Because you were from outside, it gave them space. For example, an indigenous woman talked about how she found it hard to trust. This surprised some people. I am sure she had said this before, but she had not been heard.”

These two trustbuilders agree that it will be important to avoid blame and shame. “With this program we need to be very factual and make room for people to tell their stories in ways that are really heard. We need experience supported by facts.”